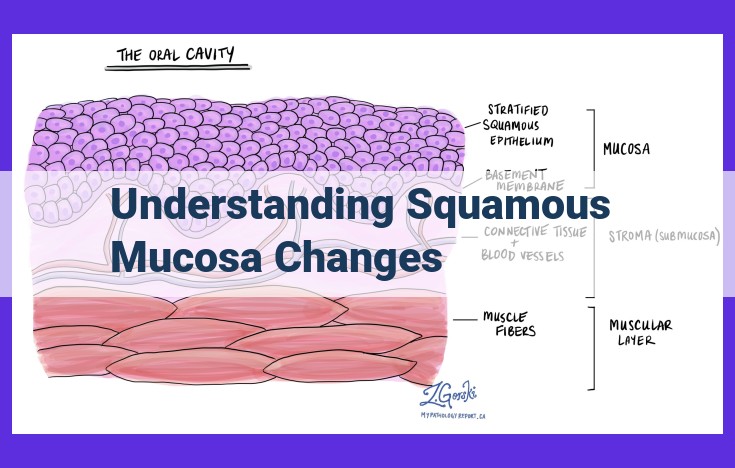

Understanding squamous mucosa changes involves recognizing a series of alterations that can occur in this type of epithelium, located in various body regions. These changes range from squamous metaplasia, where normal epithelium is replaced with stratified squamous epithelium, to more advanced stages like hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and dysplasia. Progression through these changes may ultimately lead to carcinoma in situ, where abnormal cells are confined to the epithelium, and finally to invasive carcinoma, where cells penetrate the basement membrane and invade surrounding tissue. Comprehending this sequence is crucial for early detection and appropriate management of these mucosal changes.

The Alarming Progression of Squamous Mucosa: From Normalcy to Malignancy

Our bodies are composed of various types of tissues, each with unique functions and characteristics. One such tissue is squamous mucosa, a thin and delicate lining that covers the surfaces of our internal organs, including the mouth, esophagus, and vagina. Typically, squamous mucosa is composed of multiple layers of flat, scale-like cells that provide a protective barrier against external insults.

However, under certain circumstances, squamous mucosa can undergo a series of alterations that, if left unchecked, could lead to serious health consequences. These changes range from mild thickening to full-blown cancerous transformations. Understanding the potential progression of these changes is crucial for early detection, prompt treatment, and improved outcomes.

Squamous Metaplasia: A Tale of Cellular Transformation

In the realm of our bodies, where cells dance and adapt, a fascinating tale unfolds within the delicate lining of our tissues known as squamous mucosa. Under certain circumstances, this mucosa embarks on a remarkable journey of transformation, transitioning from a specialized epithelium into a different form altogether: stratified squamous epithelium.

What is Squamous Metaplasia?

Imagine a tapestry woven with intricate threads representing our cells. Squamous metaplasia occurs when the normal threads of epithelium, responsible for keeping our tissues moist and protective, are replaced by a new pattern: the layered threads of stratified squamous epithelium. This transformation often occurs in response to environmental stressors, such as chronic irritation or inflammation, like a pebble thrown into a tranquil pond.

Causes and Significance

The reasons behind squamous metaplasia are as varied as the tissues it affects. Friction, pressure, chemicals, and even certain infections can trigger this cellular metamorphosis. Its significance lies in its role as a precursor to more dramatic changes. By understanding the process of squamous metaplasia, we can identify and address underlying issues before they progress into more serious conditions.

A Precursor to Further Alterations

Like a ripple effect, squamous metaplasia can set in motion a series of events that culminate in more advanced changes within the tissue. It often serves as a stepping stone towards hyperkeratosis, a thickening of the outermost layer of the epithelium, and acanthosis, a proliferation of the prickly cell layer beneath. These alterations, though subtle, subtly pave the way for the development of dysplasia, a more severe abnormality where cells begin to lose their normal characteristics and arrangements.

Hyperkeratosis and Parakeratosis

- Describe thickening of the keratin layer and retention of nuclei in the keratin layer

- Explain causes and potential link to squamous metaplasia

Hyperkeratosis and Parakeratosis: Thickening and Nuclear Retention in Squamous Mucosa

As we continue our exploration into the series of changes that can affect squamous mucosa, let’s delve into two fascinating phenomena: hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. These conditions involve thickening of the keratin layer, a protective barrier that shields the underlying epithelial cells from wear and tear.

Hyperkeratosis: Excess Keratin Production

Hyperkeratosis occurs when the production of keratin, a fibrous protein that strengthens the skin, becomes excessive. This results in a thickened stratum corneum, the outermost layer of the epidermis. Hyper means “excessive,” and keratosis refers to the formation of keratin.

Causes of Hyperkeratosis:

- Chronic rubbing or pressure

- Sun exposure

- Skin injuries

- Some skin disorders, such as psoriasis

Parakeratosis: Incomplete Keratinization

Parakeratosis is a distinct condition characterized by incomplete keratinization. Normally, the nuclei of epithelial cells disintegrate as they differentiate into keratin-filled cells. However, in parakeratosis, these nuclei persist within the keratin layer. Para means “abnormal,” and keratosis again denotes the presence of keratin.

Causes of Parakeratosis:

- Rapid cell turnover

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Some skin diseases, such as eczema

Potential Link to Squamous Metaplasia

Interestingly, both hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis have been linked to a condition called squamous metaplasia. This is a change in the type of epithelial cells that line a surface. Normally, squamous mucosa is composed of flat, scale-like cells. However, in squamous metaplasia, these cells are replaced by stratified squamous epithelium, a thicker and more durable type of tissue.

Hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis can contribute to squamous metaplasia by creating a favorable environment for the growth of stratified squamous epithelium. They provide a thicker and more protective barrier, which can protect the underlying cells from damage. This can lead to a gradual shift from normal squamous mucosa to stratified squamous epithelium, a process known as metaplasia.

**Acanthosis: A Thickening of the Skin’s Prickle Cell Layer**

Acanthosis is a condition characterized by an abnormal thickening of the prickle cell layer in the skin. This layer is located beneath the outermost layer of the epidermis and consists of elongated cells connected by bridges called desmosomes. In acanthosis, the prickle cells become enlarged and disorganized, leading to a thickening of the layer.

This thickening is often triggered by chronic irritation or inflammation of the skin. Common causes include:

- Psoriasis: A skin condition that causes red, scaly patches

- Lichen planus: A chronic inflammatory skin disease

- Eczema: A group of skin conditions that cause itchy, inflamed skin

Acanthosis is typically diagnosed through a skin biopsy, in which a small sample of skin is removed and examined under a microscope. It is important to distinguish acanthosis from squamous cell carcinoma, a type of skin cancer that can also cause thickening of the skin.

The presence of acanthosis may indicate an underlying skin condition that requires treatment. In some cases, topical or oral medications can be prescribed to reduce inflammation and promote healing. It is important to seek professional medical advice if you notice any thickening or changes in the appearance of your skin. By understanding the causes and potential implications of acanthosis, you can proactively care for your skin while supporting early detection and treatment of any underlying issues.

Dysplasia: A Precursor to Cancer

Dysplasia refers to abnormal changes in the characteristics of epithelial cells, the cells that line the surfaces of organs and tissues. These changes can be a precursor to carcinoma in situ, an early stage of cancer that remains confined within the epithelium.

Dysplasia is characterized by alterations in cell size, shape, and organization. The cells may appear larger and more pleomorphic, meaning they exhibit a variety of shapes and sizes. The nuclei, which contain the cell’s genetic material, may be enlarged, irregular, and contain multiple nucleoli. The normal layering of cells may also be disrupted, resulting in loss of polarity.

The causes of dysplasia are not fully understood, but it is often associated with chronic irritation or inflammation. This can occur due to factors such as smoking, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, or prolonged exposure to certain chemicals or substances.

Dysplasia is significant because it indicates an increased risk of progression to carcinoma in situ, which can further develop into invasive cancer. It is, therefore, crucial to diagnose and treat dysplasia early on to prevent its progression.

Carcinoma in Situ: A Precursor to Cancer

Squamous mucosa, a type of cell lining, undergoes a series of changes that can lead to cancer. Squamous metaplasia, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and dysplasia are all precursors to the most serious form of these changes: carcinoma in situ.

Carcinoma in situ is a form of intraepithelial neoplasia, meaning that the abnormal cells are confined within the lining of the organ. This distinguishes it from invasive carcinoma, in which the abnormal cells have broken through the lining and invaded the underlying tissue.

Early Detection and Management of Carcinoma in Situ

Despite its confined growth, carcinoma in situ is still a serious condition that can progress to invasive cancer if left untreated. However, if diagnosed and treated early, carcinoma in situ can be effectively managed.

Early detection involves regular screening tests to identify abnormal cells that may indicate carcinoma in situ. These tests may include Pap smears, biopsies, or other procedures depending on the location of the abnormal cells.

Management of carcinoma in situ typically involves surgical removal of the affected tissue. This is done to prevent the abnormal cells from progressing to invasive cancer. In some cases, radiation therapy or medications may also be used.

Importance of Diagnosis and Treatment

Understanding the sequence of events from squamous metaplasia to invasive carcinoma is crucial for early detection and treatment. This knowledge enables healthcare professionals to identify and intervene at the earliest stages, increasing the chances of a favorable outcome.

Carcinoma in situ is a warning sign that should not be ignored. Early diagnosis and appropriate management can effectively prevent invasive cancer and improve overall health outcomes.

Invasive Carcinoma

- Define invasion of the basement membrane and infiltration into connective tissue

- Emphasize its representation as the most advanced stage of squamous mucosa changes

Invasive Carcinoma: The Most Advanced Stage of Squamous Mucosa Changes

As the final and most severe stage in the series of changes that can occur in squamous mucosa, invasive carcinoma marks a significant turning point in the health of the affected tissue. This condition arises when cancer cells break through the basement membrane, the thin layer that separates the epithelium from the underlying connective tissue. This breach allows the cancer to infiltrate into the surrounding tissue, potentially spreading to lymph nodes and distant organs.

Invasive carcinoma represents the most advanced and life-threatening stage of squamous mucosa changes. Early detection and treatment are crucial to prevent further progression and improve the chances of a successful outcome. Understanding the sequence of events leading to invasive carcinoma is vital for healthcare professionals to effectively monitor and diagnose these changes in their early stages.

Squamous Mucosa and Its Potential Journey to Invasive Carcinoma

In our bodies, squamous mucosa lines various surfaces, including the esophagus, mouth, and vagina. While it serves as a protective barrier, it can undergo a series of changes that have implications for our health.

From Squamous Metaplasia to Invasive Carcinoma

The path from normal squamous mucosa to invasive carcinoma is a gradual one, potentially unfolding through the following stages:

- Squamous Metaplasia: Here, normal epithelium is replaced by stratified squamous epithelium, a precursor to further changes.

- Hyperkeratosis and Parakeratosis: The keratin layer thickens, and nuclei may be retained within it. This can result from friction or irritation.

- Acanthosis: The prickle cell layer thickens, often in response to chronic inflammation or irritation.

- Dysplasia: Epithelial cells exhibit abnormal changes, signaling a potential precursor to carcinoma in situ.

- Carcinoma in Situ: Intraepithelial neoplasia, confined to the epithelial layer, represents a stage where early detection and removal can prevent invasive growth.

- Invasive Carcinoma: Invasion of the basement membrane marks the most advanced stage, with uncontrolled infiltration into connective tissue.

Recognizing the Sequence for Early Detection and Treatment

Understanding this sequence of events is crucial for early detection and treatment. Regular examinations and screening tests can detect changes in squamous mucosa before they progress to more serious stages. By identifying and addressing these changes promptly, we can significantly improve the chances of successful treatment and prevent the development of invasive cancer.