- Introduction

- Beams

- Columns

- Deflection

- Moment

- Shear

- Stress

- Strain

- Yield

A steel beam design guide offers comprehensive guidelines for designing beams and columns to resist forces such as bending, compression, and shear. It defines key concepts, explains structural elements, and provides design methods to ensure structural integrity, safety, and efficiency in buildings, bridges, and vehicles.

- Overview of steel beam design concepts

- Definition of essential terms (beams, columns, deflection, moment, shear, stress, strain, yield strength)

Understanding the Essence of Steel Beam Design: A Comprehensive Guide

In the realm of engineering, understanding the fundamental concepts of steel beam design is paramount. These concepts underpin the design of countless structures, from towering skyscrapers to resilient bridges. Embark on this journey as we unravel the intricacies of steel beam design, shedding light on essential terms that define the field.

At the core of steel beam design lies the understanding of structural elements that bear the brunt of loads: beams and columns. Beams, the horizontal components, endure bending forces, while columns, their vertical counterparts, withstand compression. Their design centers around resisting these forces effectively.

In this context, the term deflection emerges as a crucial consideration. It refers to the displacement of beams and columns under load, influenced by factors such as their stiffness, load magnitude, and length.

Another fundamental concept is moment, the force that causes rotation. Moments arise when forces act at an offset from a structure’s centroid. The magnitude of a moment is determined by the force’s magnitude and its distance from the centroid.

Alongside moment, we encounter shear, a force that causes material to slide. Shear is induced by parallel forces to the cross-section, with its magnitude dictated by the force’s magnitude and the cross-sectional area.

At the micro level, materials experience stress, an internal force per unit area induced by applied loads. Strain, the corresponding deformation per unit length, is a direct consequence of stress and is influenced by the stress magnitude and the material’s modulus of elasticity.

Finally, yield strength holds a vital role in design. It represents the stress at which plastic deformation commences, thus defining the maximum stress a material can withstand without permanent deformation.

Beams

- Structural elements subjected to bending

- Function in buildings, bridges, vehicles

- Design to resist bending moments

Understanding the Fundamentals of Steel Beams: Design Concepts for Structural Integrity

In the realm of structural engineering, steel beams stand as indispensable components, their presence shaping the very fabric of our built environment. From towering skyscrapers to sprawling bridges, these versatile elements play a crucial role in carrying loads and maintaining structural stability.

Beams: The Bending Backbone

A beam, in essence, is a structural element that primarily endures bending. Picture it as a horizontal or inclined member, bearing the burden of forces that cause it to curve or deflect. These forces, known as bending moments, exert a twisting action on the beam’s cross-section.

Function and Applications

Beams find their place in a diverse array of structures, each fulfilling a distinct purpose. In buildings, they form the skeletal support system, transferring loads from floors and walls to the supporting columns. In bridges, they serve as the primary load-bearing members, carrying the weight of vehicles and pedestrians alike. Even in vehicles, beams find application, providing structural integrity to frames and chassis.

Design Considerations

When designing steel beams, engineers must meticulously consider their ability to resist bending moments. This is a critical aspect to ensure the beam’s stability and prevent excessive deflection that could compromise the structure’s functionality and safety. The beam’s cross-sectional shape, material properties, and length all play a significant role in determining its bending strength.

Columns: The Pillars of Structural Integrity

In the realm of structural engineering, columns stand tall as the vertical pillars that bear the weight of imposing structures, from skyscrapers to bridges and towers. These essential elements work tirelessly to resist the compressive forces that threaten to crush them.

Columns find their roles in various architectural marvels, including:

- Buildings: As upright supports for floors, roofs, and walls.

- Bridges: As pillars that hold up the roadway, allowing vehicles to traverse vast distances.

- Towers: As lofty structures that reach towards the heavens, providing panoramic views.

The design of columns is a meticulous process, focused on ensuring their ability to withstand the axial loads that they bear. Engineers carefully consider the material properties, cross-sectional shape, and length of the column to optimize its strength and stability.

Material properties play a crucial role in column performance. Steel is a popular choice for columns due to its high strength-to-weight ratio and resistance to corrosion. Concrete, another common material for columns, offers durability and fire resistance.

The cross-sectional shape of a column affects its load-bearing capacity. Solid circular or square sections are ideal for concentrated loads, while hollow sections can provide efficient support for distributed loads.

Length is another critical factor in column design. Longer columns are more susceptible to buckling, a sudden failure that occurs when the column bends under excessive load. Engineers use bracing or reinforcement to prevent buckling and ensure the stability of columns.

Deflection

- Displacement of beams and columns under load

- Influenced by stiffness, load magnitude, and length

Understanding Deflection in Steel Structures

Deflection, a crucial concept in steel beam design, refers to the displacement of beams and columns when subjected to imposed loads. It’s a critical factor that engineers consider to ensure structural integrity and prevent excessive deformation.

Factors influencing deflection include the stiffness of the steel, the magnitude of the load, and the length of the structural element. Beams and columns made of stiffer steel, such as high-strength alloys, exhibit less deflection under the same load conditions. Similarly, reducing the applied load reduces deflection.

Understanding the relationship between these variables is essential for designing steel structures that meet safety and performance requirements. Excessive deflection can lead to structural instability, damage to non-structural components, and discomfort for occupants. Engineers employ various design techniques to minimize deflection, such as utilizing stronger steel sections, increasing the moment of inertia, and incorporating additional support elements.

By carefully considering deflection, engineers can create steel structures that endure the rigors of external forces while maintaining their intended shape and functionality.

Moment

- Force causing rotation

- Generated by forces not aligned with the cross-sectional centroid

- Magnitude dependent on force magnitude and distance from centroid

Understanding Moment in Steel Beam Design

In the realm of structural engineering, moment plays a pivotal role in shaping the integrity and stability of steel beams. It’s a force that induces rotation, much like a force applied to a lever, causing it to pivot around a fixed point.

Origins of Moment

Moment arises when forces are not aligned with the centroid of a beam’s cross-section. The centroid is the geometric center of the beam, where all the material is evenly distributed. When a force acts off-center, it generates a moment that tends to cause the beam to rotate.

Magnitude of Moment

The magnitude of a moment is directly proportional to the force acting and the distance between the force and the centroid. In other words, the greater the force or the farther it is from the centroid, the larger the moment.

Consequences of Moment

Moment exerts a bending effect on the beam, causing it to deflect, or curve. Excessive moment can lead to excessive deflection, yielding, and ultimately, failure of the beam. Engineers must carefully calculate moment when designing beams to ensure they can safely withstand the anticipated loads.

Minimizing Moment

To minimize moment, engineers employ various strategies:

- Choosing the right beam size: A larger beam has a larger cross-section, which increases the distance from the centroid to the edges. This reduces the moment for a given force.

- Placing loads closer to the centroid: By positioning loads near the centroid, the distance between the force and the centroid is reduced, thereby minimizing moment.

- Using moment-resisting connections: These connections allow beams to rotate slightly, reducing the moment transmitted to the supporting structure.

Shear Force: The Invisible Force at Play

In the intricate world of structural engineering, where buildings and bridges stand tall, there’s a hidden force at work that plays a crucial role in their stability: shear force. It’s not as flashy as bending moments, but it’s just as essential.

What is Shear Force?

Shear force is the hidden force that opposes the tendency of materials to slide horizontally. It arises when two parallel forces act on opposite sides of a material, such as a building column or a bridge beam. The magnitude of the shear force is directly proportional to the magnitude of the forces and inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area of the material.

Understanding Shear Force

Imagine a stack of cards held together by a rubber band. If you push one end of the stack sideways, the cards tend to slide past each other. This is because the rubber band provides a shear force that resists the cards’ tendency to slide. Similarly, in structural elements like beams and columns, shear force prevents them from splitting apart under parallel loads.

Effects of Shear Force

Excessive shear force can lead to several undesirable effects:

- Shear Stress: Shear force creates shear stress within the material, which can cause it to deform or crack.

- Buckling: In columns, excessive shear force can lead to buckling, where the column bends and loses its load-bearing capacity.

- Failure: If the shear stress exceeds the material’s yield strength, the material may fail and break.

Preventing Shear Failure

Engineers carefully consider shear force when designing structural elements to ensure their safety and reliability. They use various techniques to minimize shear stress and prevent shear failure, such as:

- Reinforcing materials: Adding reinforcements, such as stirrups or webs, to increase the cross-sectional area and resist shear forces.

- Choosing appropriate materials: Selecting materials with high yield strengths to withstand high shear forces.

- Optimizing structural shapes: Designing beams and columns with shapes that effectively distribute shear forces.

By understanding and controlling shear force, engineers can ensure that our buildings, bridges, and other structures remain safe and stable for years to come. So, while shear force may not be as glamorous as bending moments, it’s an indispensable force that plays a vital role in the integrity of our built environment.

Stress: The Internal Force Shaping Structural Design

Imagine a colossal bridge towering over a mighty river, carrying the weight of countless vehicles and passengers. Or a towering skyscraper piercing the heavens, a testament to human engineering prowess. At the heart of these structures lies a fundamental concept: stress.

Understanding Stress

Stress is the internal force exerted per unit area within a material. It is the result of applied loads that cause the material to deform and change shape. The magnitude of stress depends on the strength of the load and the cross-sectional area of the material.

Stress and Structural Design

In structural design, stress plays a critical role. Engineers carefully calculate the stress levels within various components to ensure they can withstand the anticipated loads without failing. Yield strength, the point at which permanent deformation begins, is a crucial factor in determining the maximum stress a material can handle.

Visualizing Stress

Imagine a steel beam supporting a heavy load. The beam experiences bending, causing different sections of the beam to elongate or compress. The elongated sections undergo tensile stress, while the compressed sections experience compressive stress.

Stress Distribution

The distribution of stress within a component is influenced by its geometry and the type of loading. For instance, a beam carrying a point load will experience concentrated stress at the point of contact, while a uniformly distributed load will spread the stress more evenly.

Impact of Stress on Structural Integrity

Excessive stress can compromise the structural integrity of a component. If the stress exceeds the yield strength of the material, permanent deformation or even failure can occur. Engineers must carefully design structures to keep stress levels within acceptable limits.

By understanding stress and its implications, engineers can create safe and reliable structures that withstand the forces of nature and human activity for generations to come.

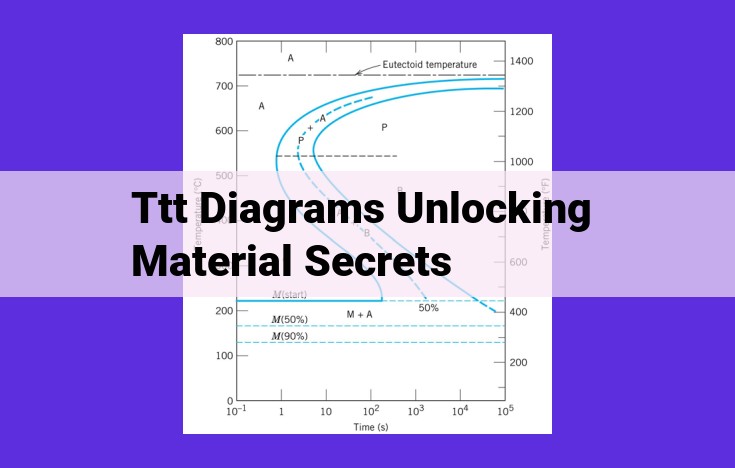

Strain: Material Deformation Under Stress

Understanding Strain

In the realm of engineering, strain plays a crucial role in comprehending the behavior of materials under applied forces. Strain refers to the deformation or change in length of a material per unit length when subjected to stress. It’s a measure of how much a material stretches or compresses in response to external loading.

Cause and Effect of Strain

Strain is a consequence of stress, the internal force exerted per unit area within a material. When stress is applied to a material, it causes the material to deform, resulting in strain. The magnitude of strain is directly proportional to the magnitude of stress.

Factors Influencing Strain

The strain experienced by a material depends on two primary factors:

- Stress Magnitude: The higher the stress applied, the greater the strain.

- Material’s Modulus of Elasticity: This property, denoted as E, represents the stiffness of a material. A higher modulus of elasticity indicates a stiffer material that resists deformation more, resulting in lower strain for a given stress.

Types of Strain

Depending on the nature of deformation, strain can be classified into two types:

- Tensile Strain: Occurs when a material is stretched, causing an increase in length.

- Compressive Strain: Occurs when a material is compressed, causing a decrease in length.

Significance of Strain

Strain is a crucial consideration in engineering design, as excessive strain can lead to material failure. By understanding the relationship between stress and strain, engineers can design structures and components that can withstand the intended loads without exceeding acceptable strain limits. It also helps in predicting the behavior of materials under various loading scenarios, ensuring structural integrity and safety.

Yield Strength

- Stress at which plastic deformation begins

- Critical property determining maximum stress with no permanent deformation

Yield Strength: The Critical Stress for Structural Integrity

In the world of steel beam design, yield strength holds a crucial place. It is the stress at which a material begins to undergo permanent deformation, an irreversible change in its shape. Understanding yield strength is essential for ensuring the safety and integrity of structures, especially those made of steel.

Stress and Strain

Imagine a beam under the weight of a heavy load. The beam experiences stress, which is the internal force acting on its surface per unit area. As the stress increases, the beam will deform or stretch, which is known as strain.

Elasticity and Plasticity

Steel exhibits two important properties: elasticity and plasticity. In the elastic region, the deformation is temporary and the beam returns to its original shape when the load is removed. However, once the stress exceeds the yield strength, the beam enters the plastic region. In this region, deformation becomes permanent, as the material undergoes plastic deformation.

Importance of Yield Strength

Yield strength is a critical property that determines the maximum stress a steel beam can withstand without deforming permanently. It is crucial in the design of structures because it ensures that the beam can handle the expected loads without collapsing.

Engineers use yield strength calculations to determine the load capacity and safety factor of a beam. By keeping the stress below the yield strength, they can ensure that the beam remains intact and the structure is safe.

Yield strength is an essential concept in steel beam design. By understanding this property, engineers can design structures that are strong, reliable, and safe. Yield strength ensures that steel beams can withstand the rigors of daily use and protect people and property from structural failure. It is a testament to the importance of structural engineering and the vital role it plays in the safety and integrity of our built environment.